Hospital

02 February 2026

02 February 2026

Home, last summer. If anyone had suggested I ‘think of a happy place’, this would be it. Olympus OM-1, Kodak Portra 400

Home, last summer. If anyone had suggested I ‘think of a happy place’, this would be it. Olympus OM-1, Kodak Portra 400

I remember almost every detail from that day at the hospital, but what I find myself thinking about most often is the gap in between—the episode that I have no knowledge of. I remember being transferred to the OR, a room that looked like the command centre of a spaceship, or a data centre in the middle of moving house. Impressive, and slightly intimidating. I climbed onto the operating table, half naked, where they placed warm and cold patches on my body, a nose mask over my face for oxygen, and positioned me exactly right so that the vital inner parts of my body would be visible on a monitor at my feet. All very efficient and routine. One of the doctors made small talk with me. In hindsight, I would have preferred to properly take in everything that happened in that room, but at that very moment, I appreciated the distraction.

As soon as the anaesthetics kicked in I was gone, only to wake up a few hours later in the recovery room. What happened in between, I don’t know. It’s the silly details I wonder about, not so much the operation itself—a fairly abstract procedure. If I could have watched it, I would have been looking at a screen. I probably wouldn’t have been able to mentally connect the visuals with my own flesh and bones.

It feels much stranger imagining how they painted my lower body parts with a disinfecting liquid that left an aggressive pink on my skin, in a better-safe-than-sorry kind of way. How they put a knife in my groin and shoved a tube into my vein, a rather intimate act I would say. What would they have said to each other? What would my face have looked like? Like I was sleeping? Or dead? How many of them were needed to get me back into bed? Two? Four? Would my limbs at least have cooperated a little? Somehow, they managed to make me presentable again. Or human, perhaps. Released my hair from the silly cap, rearranged my hospital jacket, tucked me in. It still feels a little absurd to think about these things.

As soon as the anaesthetics kicked in I was gone, only to wake up a few hours later in the recovery room. What happened in between, I don’t know. It’s the silly details I wonder about, not so much the operation itself—a fairly abstract procedure. If I could have watched it, I would have been looking at a screen. I probably wouldn’t have been able to mentally connect the visuals with my own flesh and bones.

It feels much stranger imagining how they painted my lower body parts with a disinfecting liquid that left an aggressive pink on my skin, in a better-safe-than-sorry kind of way. How they put a knife in my groin and shoved a tube into my vein, a rather intimate act I would say. What would they have said to each other? What would my face have looked like? Like I was sleeping? Or dead? How many of them were needed to get me back into bed? Two? Four? Would my limbs at least have cooperated a little? Somehow, they managed to make me presentable again. Or human, perhaps. Released my hair from the silly cap, rearranged my hospital jacket, tucked me in. It still feels a little absurd to think about these things.

Commuting

07 December 2025

07 December 2025

This may very well be my ultimate dream

scenario: to temporarily disappear to get my act together, clean out my

closets, tackle this ‘paper’work nightmare, trade escapism for discipline,

practice, practice, practice, and resurface with a magnificent series of

photographs.

For you

21 November 2025

21 November 2025

The

algorithm has zeroed in on me and is pelting me with posts from all sorts

of accounts that all look the same and always end with the line: if you’re

an introvert, this page is for you. Which I doubt.

It’s not that I don’t identify with the type, I easily do, and many of the traits listed on those pages are spot on. But at the same time—what a bland, syrupy and overly delicate picture they paint of me and my fellow introverts. As if we spend our days draped in soft beige knitwear, tucked under a blanket, journaling by dim light while “resetting and recharging” after the slightest interaction with the outside world. Staring through a fogged-up window, processing stimuli with gentle music in the background. Having to recover from every tiny disruption to our carefully cultivated routines. Maybe those pages are for me after all—to kick me out of the house.

Last Sunday I took the train to The Hague and photographed this building. Because last time the weather wasn’t cooperating and I left without any exterior shots. So now I’ve got photos of a beige building in grey, muted light, along an empty street. If you are an introvert, this post is for you.

It’s not that I don’t identify with the type, I easily do, and many of the traits listed on those pages are spot on. But at the same time—what a bland, syrupy and overly delicate picture they paint of me and my fellow introverts. As if we spend our days draped in soft beige knitwear, tucked under a blanket, journaling by dim light while “resetting and recharging” after the slightest interaction with the outside world. Staring through a fogged-up window, processing stimuli with gentle music in the background. Having to recover from every tiny disruption to our carefully cultivated routines. Maybe those pages are for me after all—to kick me out of the house.

Last Sunday I took the train to The Hague and photographed this building. Because last time the weather wasn’t cooperating and I left without any exterior shots. So now I’ve got photos of a beige building in grey, muted light, along an empty street. If you are an introvert, this post is for you.

The attic

28 August 2025

28 August 2025

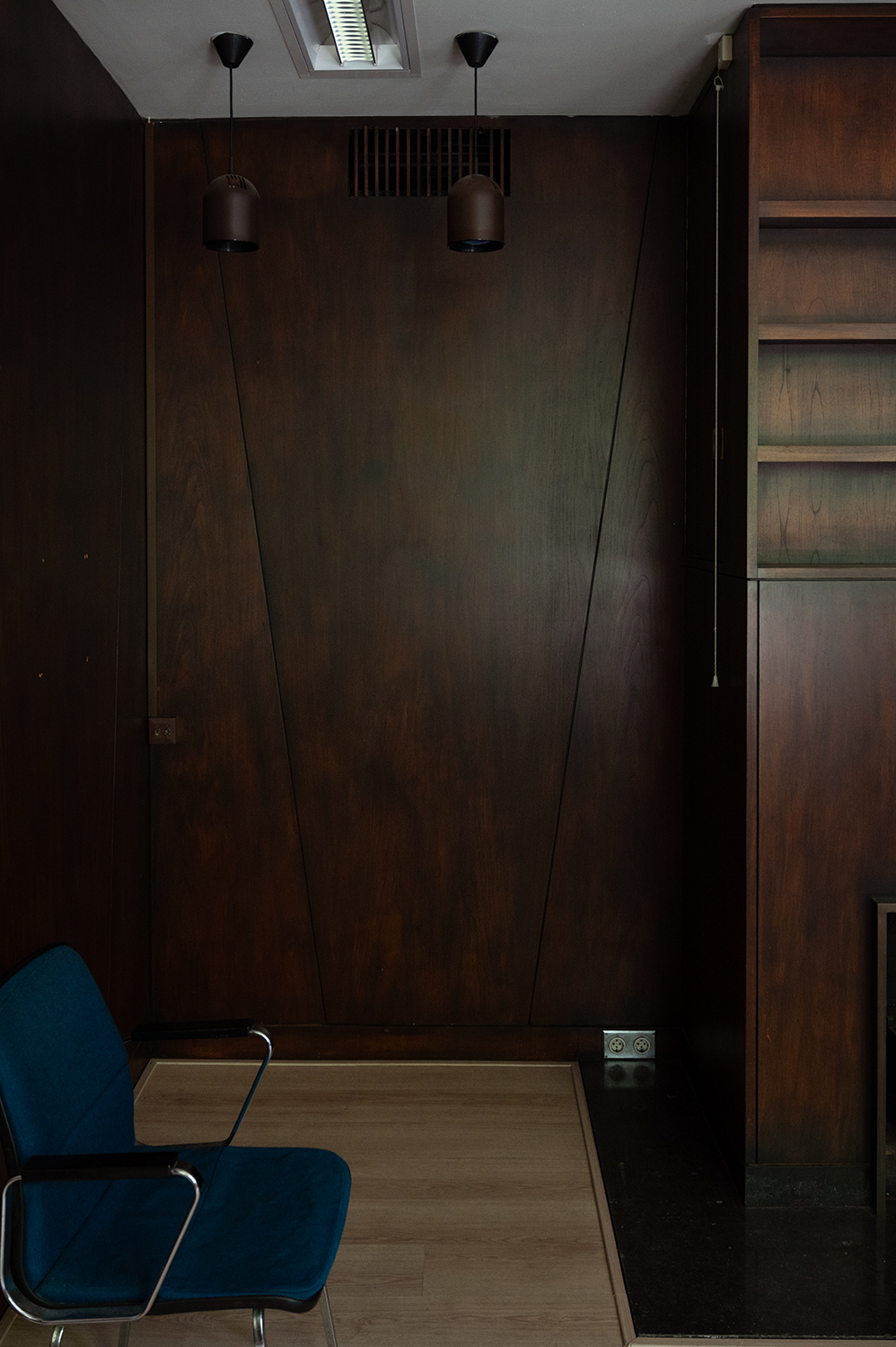

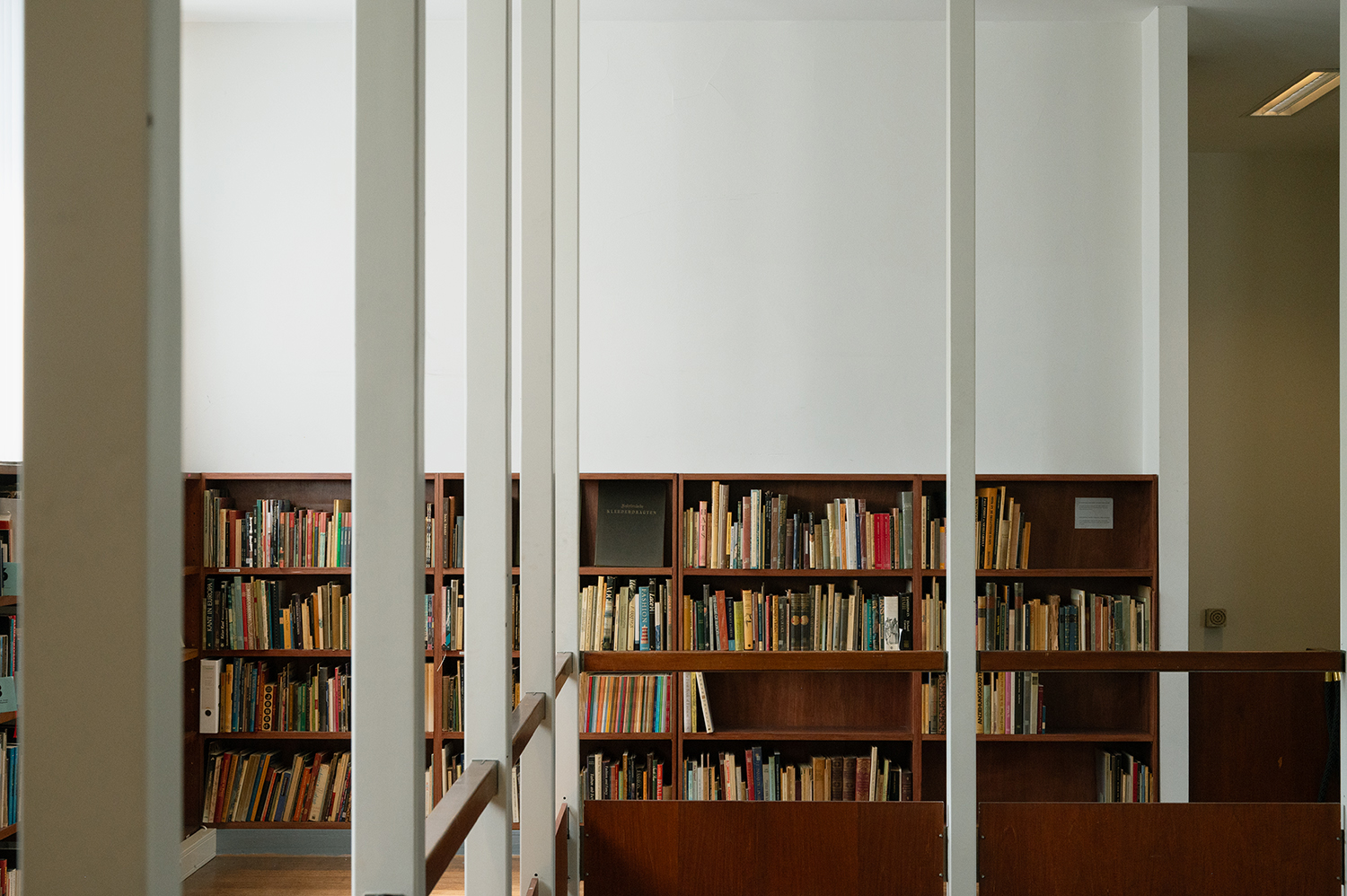

So the institute acquired the archive of Aldo and Hannie van Eyck. Physically everything is still on site where it was created: in the former house and workplace of the architects, now home to their heirs. Historically it’s not an insignificant place. The garden in the cover photo of this book, Team 10 meetings, is theirs, and the very place where I had my sandwich for lunch yesterday. I went to the house because I thought we might need some pictures of the archive in situ, before it was transported to the depots in Rotterdam. When it’s gone it’s gone. Also, I was curious.

I would be photographing in the attic, while three of my colleagues prepared the inventory. And I would take pictures of them at work as well. I didn’t know what to expect from ‘the attic’. Dark probably. Cramped, cluttered. Difficult light distribution. I brought the tripod, but I didn’t know if there was enough space to unfold it. Besides, how useful is a tripod when photographing the dynamics of people at work? I wasn’t sure. I usually photograph things that do not move, or move very, very slowly, like buildings, landscapes and interiors. Occassionally a human being is present in the frame. But for this, I imagined something less static and distant. Not being a fly on the wall, but more or less present in the process, as far as that goes.

Unfortunately I didn’t get to see the house. J. photographed it earlier this year, including the models, and before the entire art collection was sold (I believe that eventually the house itself will be sold as well). But he never made it to the attic, which is in a separate building on the same property, and nothing special, apart from the fact that it houses the archive.

(︎︎︎ Some familiar seventies items made me smile: a brown version of the green Poulsen lamp hung over our dining table when I was a child. The Boby trolley, that was my mum’s, and I had this globe-like paper lamp in my bedroom, only smaller. Isamu Noguchi vs IKEA, I presume.)

For various reasons I felt a responsibility to do this right. I would not be able to do it again, nor would anyone else. Not everything worked out well, but I’m pleased with what did. The only silly thing is that I didn’t photograph the garden.

A selection of these photographs is here to see.

I would be photographing in the attic, while three of my colleagues prepared the inventory. And I would take pictures of them at work as well. I didn’t know what to expect from ‘the attic’. Dark probably. Cramped, cluttered. Difficult light distribution. I brought the tripod, but I didn’t know if there was enough space to unfold it. Besides, how useful is a tripod when photographing the dynamics of people at work? I wasn’t sure. I usually photograph things that do not move, or move very, very slowly, like buildings, landscapes and interiors. Occassionally a human being is present in the frame. But for this, I imagined something less static and distant. Not being a fly on the wall, but more or less present in the process, as far as that goes.

Unfortunately I didn’t get to see the house. J. photographed it earlier this year, including the models, and before the entire art collection was sold (I believe that eventually the house itself will be sold as well). But he never made it to the attic, which is in a separate building on the same property, and nothing special, apart from the fact that it houses the archive.

(︎︎︎ Some familiar seventies items made me smile: a brown version of the green Poulsen lamp hung over our dining table when I was a child. The Boby trolley, that was my mum’s, and I had this globe-like paper lamp in my bedroom, only smaller. Isamu Noguchi vs IKEA, I presume.)

For various reasons I felt a responsibility to do this right. I would not be able to do it again, nor would anyone else. Not everything worked out well, but I’m pleased with what did. The only silly thing is that I didn’t photograph the garden.

A selection of these photographs is here to see.

American Embassy

07 August 2025

07 August 2025

Former American Embassy, The Hague. Built in 1959. Architecture by Marcel Breuer.